Lockdown, whatever

The plan to divert attention from Dominic Cummings worked pretty well. One notable side effect was a loss of public attention.

Dominic Cummings was never going to get the sack. There are very few people near the seat of power who combine the ideological adherence to Brexit at any cost, with the intelligence and stamina required to run a government. So he stayed in place, but with the benefit of hindsight, the price paid was a marked loss of public interest in what the government says and does. In the midst of a pandemic, maintaining public trust is important, but if you can’t manage that then you want to at least hold their attention. Cummings’ ill-judged visit to Barnard Castle during Lockdown made the public switch off.

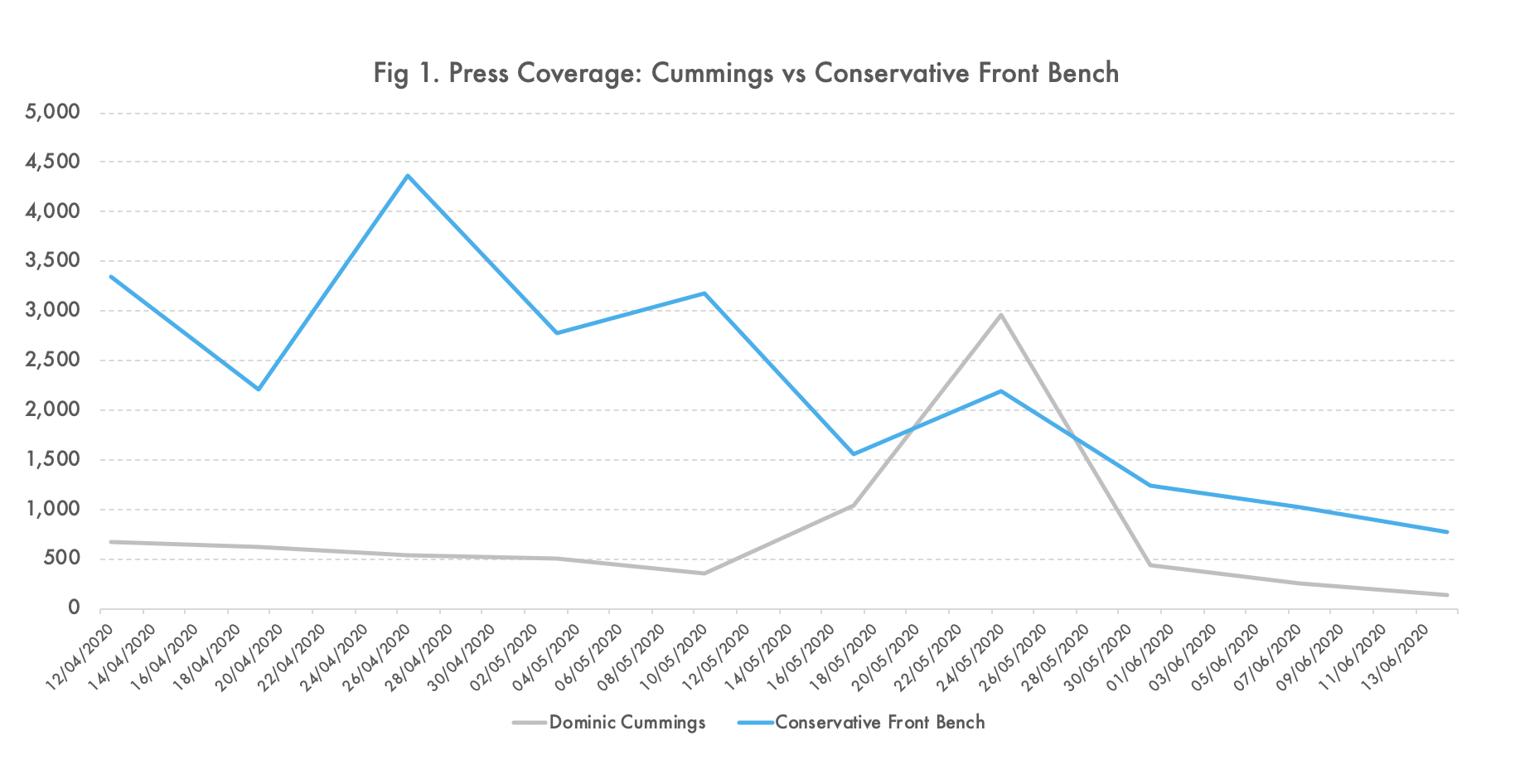

We looked at two key metrics over a period of 10 weeks: Coverage, and Public Interest. ‘Coverage’ is a simple count of news articles, blogs and video clips published in relation to the Conservative front bench (including Johnson himself, Health Secretary - Matt Hancock, Chancellor of the Exchequer - Rishi Sunak, Cabinet Secretary - Michael Gove, Foreign Secretary - Dominic Raab and Home Secretary - Priti Patel), vs Dominic Cummings. The second measure - ‘Public Interest’ - is based on how many times articles or videos about either the front bench were shared, vs how many times pieces about Cummings were shared. Sharing is a key online behaviour because it indicates a very high level of interest (see Signify’s proprietary ShareScore technology):

Fig 1: Comparing column inches for the government, vs Cummings over 10 weeks

The 10-week period we looked at includes the week after Boris Johnson was discharged from hospital, riding a wave of global media interest and public goodwill. Within a month, the actions of his Special Advisor eclipsed not only coverage of Johnson, but media coverage for the entire front bench, for nearly a fortnight (see Fig 1 above). Important announcements about schools re-opening and relaxing rules on social distancing eventually drove Cummings out of the headlines – but these should have been significant morale boosting moments, and instead felt like diversions. Public attention followed in-line with media coverage, showing no perceptible spike in interest for government announcements in the wake of the scandal.

Fig 2: Public interest in Cummings scandal waned as media moved on

In any normal government, the moment when Cummings displaced Johnson in terms of personal column inches (see Fig 3 below) is the point at which the Special Adviser would have resigned. But these are not normal circumstances, so the cabinet instructed the country, and the media to move on and put their focus back onto CV-19 recovery efforts. (For clarity, we didn’t compare actual column inches. The graph below shows the number of news articles, blogs and video clips from news outlets, posted about the two men.)

Fig 3: Cummings eclipses Boris

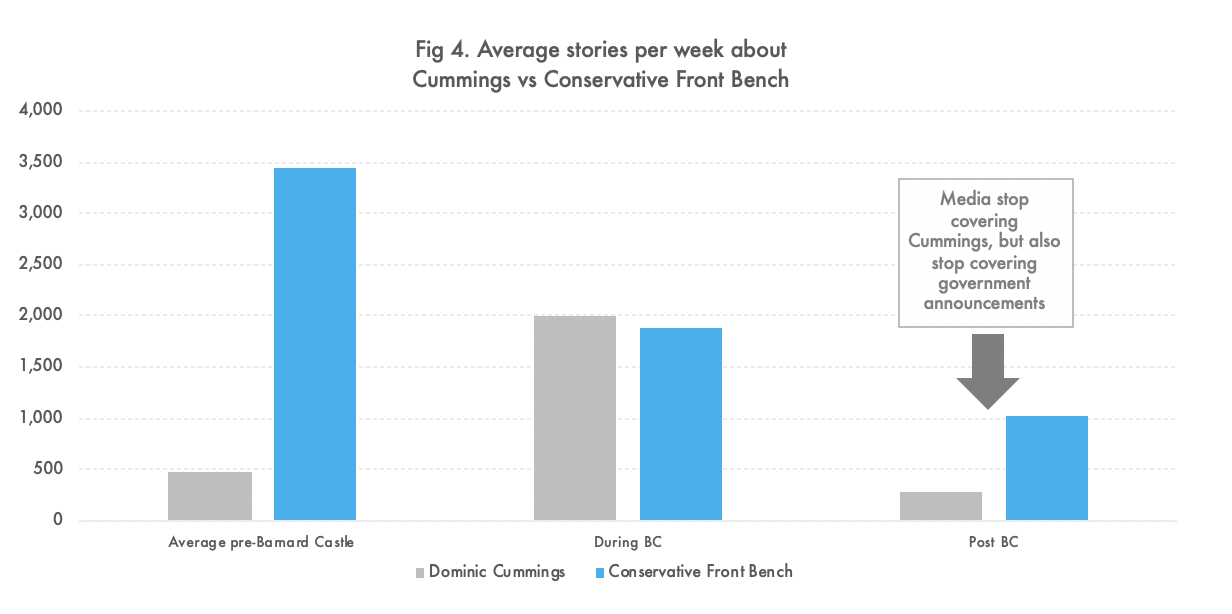

To be fair to the government, there are certainly more pressing issues to worry about than the day trips taken by one SPAD during lockdown. But, our data clearly shows that the cost in credibility has been high – both in terms of media coverage, and public interest. Fig 4 below shows media coverage for a period of three weeks before and after the Cummings scandal. Online media coverage of the entire Conservative front bench dropped from over 3,000 articles per week pre-scandal, to less than 1,000 per week after Barnard Castle. Some of this no doubt reflects exhaustion with the daily briefings. But the loss of media interest in announcements by the government also reflects a loss of credibility. Whatever the cause, Cummings’ actions eclipsed and debilitated the government at a critical time.

Fig 4: Media loses interest in government narrative

Finally, we see an even more precipitous collapse in public attention to stories and video clips about the government’s response to COVID-19. This reflects the experience of everyone who lived through those weeks in the UK; if government ministers are ready and willing to talk what many have perceived as nonsense on live television, what’s the point in listening to them?

Fig 5: Public stop sharing news about CV-19 policy

At a time when credibility is more important than ever for the Government, this data indicates that the decision not to sack Dominic Cummings may have undermined public faith, trust and interest in government policy, including their efforts to help the country back on its feet.

Caveat/Disclaimer: This study is based on public published media and sharing data. According the the same metrics, there was a huge surge in public interest in the government a fortnight after the period covered here. However, this was driven by Dominic Raab’s apparent belief that “taking a knee” is a reference to the TV show Game of Thrones, rather than being popularised by US athletes, notably the American football player Colin Kaepernick, as a protest against racism and police brutality.

Signify is an ethical data science company with clients in politics, media, finance, higher education, sport and the charity/NGO sector. Read more about our work.

(Picture credit: Sky News)